How important is the narrative?

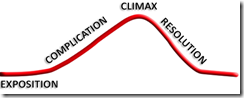

11 Comments Published by Colin Wyers on Sunday, March 30, 2008 at 12:11 PM.If you think back to your high school lit classes, you may dimly recall something called the narrative arc:

- Exposition

- Complication

- Climax

- Resolution

It might seem more familiar if I go ahead and diagram it out for you:

That's why it's called the narrative arc - you have your rising action and your falling action. It's not quite a bell curve - the slope on the left is more gradual than the slope on the right.

This has been around pretty much since Aristotle; it's an abstraction but a useful one nonetheless.

Let's apply this to Casablanca real quick, just to make sure we understand how it's supposed to work. Exposition? Explain the political situation in France and its territories, the existence of Rick's bar (and Rick), and then set up the bit about the letters of transit. Complication? The old love interest reappears in his life, looking for those letters of transit. Climax? He puts her on the plane. Resolution? "Louis, I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship."

Yep, we've got it.

Well, baseball is an endless source of narrative arcs. An individual plate appearance can be looked at as a narrative arc, the battle of pitcher and hitter; if the hitter starts fouling off pitches and really working the count, a single at-bat can take on an epic quality, especially if the game situation adds a bit of drama to the outcome.

You can find narrative arcs in entire seasons - the 2007 Mets "choke job" is the first that comes to mind - or even the entire history of a franchise - 100 years of futility, anyone?

But by far the most common narrative arc of baseball is a single game, and its most frequent chronicler is the beat writer. Let's take a look at today's (or yesterday's, I guess) Cubs/Brewers tilt, first from the Chicago Tribune:

When Kosuke Fukudome hit a three-run homer off Milwaukee closer Eric Gagne to tie the season opener in the bottom of the ninth inning Monday, fans all over Wrigley Field held up professionally made signs with English words on one side and Japanese on the other.

It was meant to be a two-sided version of the phrase "It's Gonna Happen." But something got lost in translation, and the Japanese side read: "It's An Accident."

Fukudome's heroics were no accident, but they wound up going to waste when Tony Gwynn Jr. hit a sacrifice fly off Bob Howry in the 10th to lift the Brewers to a 4-3 victory on a long, soggy afternoon."It was a good ballgame," manager Lou Piniella said. "It was well-played, tough conditions. But somebody had to win, somebody had to lose, and they won the ballgame."

Fukudome went 3-for-3 with a walk. He doubled to the center-field wall on the first major-league pitch he saw and earned salaams from fans in the right-field bleachers for his stunning debut.

But the day was a total downer for Carlos Zambrano, who remains winless in four Opening Day starts and left in the seventh inning with forearm cramps. And for Kerry Wood, who allowed three runs in the ninth in his debut as the Cubs' closer.

It's the narrative arc of a tragedy; Fukudome carries the team to a great height, only to witness a greater fall.

Let's take a look at things from the other side, in the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel:

When Tony Gwynn Jr. arrived in spring training more than six weeks ago, he set an ambitious goal for himself.

Upon learning he'd be in the Milwaukee Brewers' starting lineup at the start of the season, Gwynn set another lofty goal.

"Goal No. 1 was to be in the opening day lineup," said Gwynn, who earned the right to start most days in center field while Mike Cameron is serving a 25-game suspension.

"Goal No. 2 is to be productive with the time I get, while 'Cam's' out."

The 25-year-old son of a Hall of Famer took a nice first step in that direction Monday in helping the Brewers pull out 4-3, rain-interrupted victory in 10 innings over the Chicago Cubs in the season opener at Wrigley Field.

It's more of a melodrama: largely unsung bench player makes the most of his opportunities, becoming the surprise hero of the Brewer's great victory over evil.

In baseball, there are other ways of representing the narrative arc rather than simply writing them out. Scorecards and other play-by-play accounts are becoming more common, but newspapers gave us the most iconic representations of baseball as numbers and codes: the linescore and boxscore.

Now, when we discuss baseball statistics, what we're really talking about is an aggregation of these records; we take the events and collect them. That's true about the old-school triple crown stats - batting average, home runs and runs batted in - or the "new age" VORP and Win Shares. Baseball statistics are, at their heart, simply a summary of what occurred on the field of play.

But when we collect statistics in that way, we tend to do so in a way that dissociates them from their narrative context. A player's VORP counts hits against a hated division rival in the midst of a tight race exactly the same as hits against a 30-year-old journeyman pitcher playing out the string for a basement dweller in September. Baseball statistics don't seem to have any understanding of the fact that Yankees players are attractive, handsome stars, and that Kansas City Royals players... aren't. There isn't a baseball stat that measure how athletic and, really, balletic Derek Jeter looks when he does that mid-air throw or dives for a ground ball.

And yet all of those things are important, if not essential, in forming a narrative of a baseball season. All of those things add a sense of excitement and drama to baseball. And they're the things that first attracted most of us to baseball - yes, even the Dread Sabermetricians.

If you really want to drop some chum into the water, simply mention the word "clutch" and watch the feeding frenzy begin. I've been up to my eyeballs in clutch recently - all the way from NSBB to BTF to Tango's site. I'm pretty sure that the sacking of Carthage occurred over less than what happened in the Baseball Think Factory thread.

It's an argument that I don't think will ever fully be resolved, and I'm starting to think it's because of a very narrative point of view on the part of people who are the most ardent supporters of the idea that clutch hitting has to exist.

Because in the narrative, clutch hitting does have to exist. If you're trying to boil a ballgame down to a simple narrative - and it has to be a simple narrative; newspaper stories about baseball games aren't particularly long or in-depth, and highlight reels are even less detailed - then you are boiling the game down to a handful of plays, and thus making those plays stand in for the entire game. You create heroes and villains, successes and failures, tragedies and comedies.

In the narrative, you have to have clutch. Have to.

And you need the narrative - there's a reason that you find more recreational baseball analysis than you do recreational analysis of the derivatives market. But in the end, the narrative is an intensely personal thing - Cubs fans and Brewers fans hardly share the same narrative about tonight's game, even if they witnessed the exact same events. The narrative can't hold a larger meaning, because the narrative is not an objective fact; the narrative is a subjective expression of an individual or collective - but NOT universal - experience.

The narrative is also the product of two conveniences - if I was being uncharitable I would call them lies, and I'm open to being uncharitable if it will help explain the point.

Let's take a look at today's ballgames according to Fangraphs. What we're looking at are graphs of Win Probability, the closest thing sabermetrics has to a truly narrative statistic. What you'll note is that none of those graphs seem to match the shape of our narrative arc graph from earlier - for one, all of them are much more jagged. The narrative arc is neat, tidy - a real baseball game is a much more varied experience than a simple arc; the phrase "roller coaster" is cliched, but there really is no better explanation.

But the narrative conveniences of the ways we experience the game - whether it's the AP recap in the morning paper, or the highlight real on Sportscenter - don't have room for all of those nuances, all of the twists and turns and red herrings that actually happen. On the other hand, those conveniences exist because most of us simply don't have time to watch each and every ballgame; they're shortcuts and conveniences, standins for the reality underneath.

So the first lie is that you can sum up a ballgame in four or five plays. Did the Cubs lose because Bob Howry allowed one run in the tenth inning, or because for eight innings the Cubs didn't score any runs at all? Howry's charged with the loss in the boxscore, but I suspect a lot more of the "blame" should be shouldered by the lack of production pretty much all up and down the lineup.

The other lie is the emphasis on driving in runs. You will sometimes see token acknowledgement of Runs as the counterpart to Runs Batted In - especially for leadoff hitters with added entertainment value as stolen base threats - but you'll rarely, if ever, see an MVP trophy awarded for it.

Absent the thrill of the stolen base, setting the table is a lot less exciting narratively than clearing it - an RBI single is a lot more fun to watch than the walk that preceeded it. But it's not any more valuable to the team; one does not exist without the other. And yet fame, money and awards seem far more drawn to players who drive runs in rather than players who score them.

I don't want to come off as underrating the importance of the narrative point of view - I am probably the least rational person possible when it comes to actually watching a baseball game. (I think I'm still traumatized by the memory of Roberto Novoa, just to name an instance.) But it's foolish and dangerous to use it as the ONLY context through which you view baseball.

This isn't a cry for fusion, or balance, or peaceful coexistence. The world wouldn't be a better place if newspaper articles all read "Today the Cubs and Brewers recorded 27 outs apiece in a contest at Wrigley Field, which revealed almost nothing about the two teams due to the small sample size involved." Nor would the world be a better place if VORP started including Steely-Eyed Resolve as one of its components.

What I am asking for is a simple truce: believers in clutch, I as a student of sabermetrics will stop telling you that clutch doesn't exist, or is insignificant, or what have you, if you will stop insisting that its existence in any way, shape or form has an impact on impartial evaluations of player performance. Do we have a deal?

Labels: Baseball

Approve 100%

Awesome Colin. Very awesome, well done!

Completely agree. This was a great post, and I'm equally as intrigued by the fan graph site you linked to.

Byron

OK, I've never had a problem with either the narrative or the calculator crowd, but how do I make a truce with myself?

In baseball, a .300 BA is very good, very respected, maybe even sacrosanct. I've grown up with that belief -- no sabrematrician has to convince me that a .300 hitter is good.

Felix Pie hit over .300 this spring. Really good. But...

His swing is ugly. Not as ugly as it used to be, but ugly. Worse than my swing "ugly". An "ugly" that a sabrematrician can't measure.

How do I weigh the quantitative results of ST against the qualitative view of my own eyes?

Holy shit, dude. Awesome. Totally awesome.

Very nice post Colin. Agreed that those who must frame things as a story simply cannot resort to numbers.

yes yes yes! Great job Colin!

Really enjoyed this. Saw it mentioned at tangotiger's blog. I have heard that human beings are hardwired for narrative, that our brains like it or recognize it. I don't know if that comes from evolution or something else. Maybe being hardwired for narrative helps us make sense of a complicated world (as numbers do). Maybe both approaches add something to that understanding in a different way.

I have heard that a myth is "a lie on the outside but true on the inside." As Steven Landsburg wrote in the book "The Armchair Economist," there never was a hare who raced a tortoise but the moral that slow and steady wins the race is often true.

A good, clear story is a model of reality. And equations are models of reality. I don't know which one works better. They both illuminate but perhaps in different ways.

indeed, a great post—underlying a narrative is causality and this causality only becomes apparent after the fact. clutch hitting can and does exist—any hit with the game on the line can be called clutch. clutchness as a narrative is quite interesting—it is the reason sports are entertainment (the big hit, the great play)...however it is oblique. i cannot say with any confidence that pierre won't come through or that pujols will, but based on their typical metrics (average, slugging, hell even rbi's) i know which one i'd rather not face. clutch (or lack thereof) is always post hoc. the statistician would be foolish to quantify it and then predict future outcomes based on this clutch metric. it is quite possible that some people are more frazzled than others when batting with the game on the line while others approach it the same. but as such clutch may just be not non-clutch...how could you ever tell the difference?

i should also point out that language itself is an abstraction, and clutch is by no means definite before it happens. so one person's idiolect colors their interpretation. take my last sentence, many of my professors would tell me that it's a grammatical error (pronoun agreement!) whereas for me 'their' is not marked as plural and the feminist debate of linguistic determinism has pushed my generation to use 'their' in place of 'his' (sexist) and 'his or her' (awkward)—thus the lament of the present state of english. i see much of the clutch debate to hinge on its definition.

Great stuff -- one of the those "why didn't I think of that" reads.

I think the narrative arc can explain the infatuation with RBIs, too. Getting on base and advancing runners aren't that thrilling. But once the run-scoring hit occurs, BOOM. RBIs come in big batches, while runs for individual players are scored one at a time.

i was checking out random highlights and in the second reds game of the season, edwin encarnación tries to bunt with men on first and second, bottom of the ninth, and racks up two strikes...so while the camera pans to dusty giving signals (presumably 'swing away'), the announcers are saying stuff like, "you know, i look at his numbers and he is just not a clutch hitter...there's nothing clutch about him"—swing, line drive into the seats, dusty's first win as a red—the one announcer remarks (in the obligatory excited disbelief) "was that clutch!?" now if encarnación does this a few more times this month, dusty's gonna have himself the reds mvp (then he can suck it up for the rest of the year). edwin will be known hereafter as mr clutch